Prologue: I’m here revisiting an old draft. Like many of the things I write, they got lost or never shared. Whether that’s because of my own insecurity or it remains locked away in my notes, a journal, or the drafts.

It’s been over two years since I started this space. I think it’s become less about others and more about myself.

A week from now, I’ve been asked to participate in a panel for graduate students at San Francisco State University. Although it’s just a small class panel of teacher-ed students, it pushed me to look back at things I’ve written. The reason I chose to create this blog or my website was for this exact purpose. To create a resource for those lost like myself.

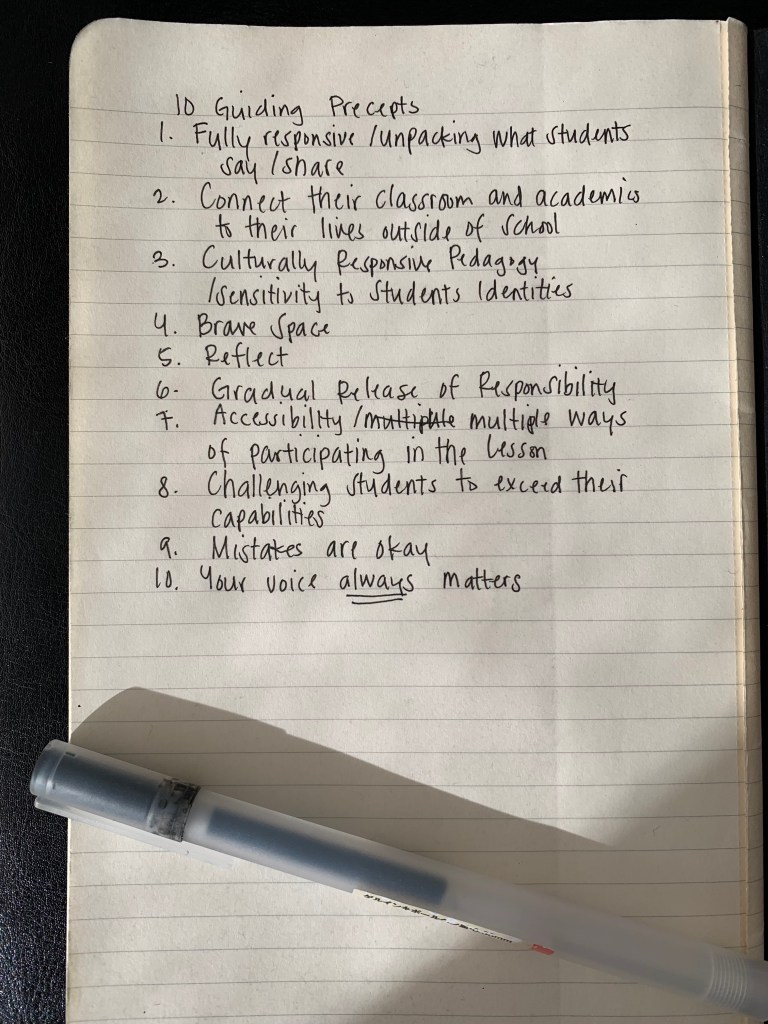

I re-opened old field notes, reflections, journal entries, old drafts. I even re-read things I’ve posted here. Revisiting these old pieces shows how valuable some of my pedagogy’s guiding precepts/core vaules have not changed. But they also show a lot of growth to where I am today as an educator. The nostalgia made me eager to find these 10 guiding precepts that my mentor/professor had us lock in during our fieldwork. I knew I started a draft somewhere. And it turns out it’s one of the oldest drafts I have:

Jan. 2020

During my last semester of undergrad (Dec 2016), my previous mentor teacher had gotten hired to be the professor of my last fieldwork course. I don’t remember everything, but I remember being upset that I had to basically retake Fieldwork I/II again. I didn’t fail or anything, it was just that I was graduating in the Fall. Being a transfer student and then changing majors after transferring didn’t place me in an appropriate cohort. So I was always in between graduating classes. I was graduating later than my anticipated date, but earlier than when Fieldwork III is offered in the Spring, so the university required that I take I/II again in place of III.

I took Fieldwork I/II under my professor when she was my mentor teacher the previous Fall semester. So instead of being a new brain for molding or a student looking for guidance, she knew I didn’t need to be in class. Instead, I became her TA at times or she would rely on me to help guide the trajectory of the course since it was her first semester teaching at the university level.

It’s always the courses you least expect that teach you the most

I wasn’t expecting to get anything out of this course, and I don’t think my professor did either. Another obstacle that inhibited my graduation was that I never completed a middle school observation, despite the School of Ed telling me I didn’t need to. I was already a volunteer teaching at another high school outside of this fieldwork, but according to policy, they wouldn’t let me substitute my teaching or observing at that site for the middle school requirement.

This final Fieldwork really took a toll on me, having to balance undergrad classes, grad classes, volunteer teaching Filipino American Studies at one high school, my part-time job, and then these middle school observations. But I actually got a lot out of this middle school placement. The teacher, the way they taught, and the environment affirmed what I needed to make sure I did that she did not. Over course of the semester, we were required to have completed at least 5 observation reflections.

“Objective: Hone your observational skills by collecting evidence of what you are seeing/hearing/experiencing in the placements and begin to shape the vision for your classroom.”

Kory O’Rourke

We were instructed to take note of the following:

- Best practices (teaching tips, tricks, and hacks)

- “I can’t believe I just heard” – Astounding (+/-) comments from students/teachers

- Classroom and school culture (evidence of the elements that build culture)

- School and Classroom Physical Space and Signage (Ex: “Ms. Orner is Reading…”)

- Professional development: What does it look like at your placement school?

- Collaboration: How do teachers collaborate together at your placement school?

- Classroom management strategies

- Modifications, accommodations, and interventions

- Questions with which you are engaged as a part of your placement

and turn, “The final pages of your notebook MUST INCLUDE your top 10 guiding precepts for your teaching/classroom.“

Kory O’Rourke

Most of these 10 precepts are things that I already had developed through my Filipino American Studies teaching program, an after-school tutoring program & teaching fellowship, and my other grad classes. But like I mentioned earlier, here are some anecdotes as to why this fieldwork solidified these 10 precepts:

Feb. 2022

To be honest, I don’t remember all the anecdotes I wanted to tell. I mentioned in 2020 the middle school fieldwork placement I was assigned to. I had a mentor teacher who was a Harvard graduate. She taught the middle school’s English & History classes. So you could really label her as a humanities teacher. It was an interesting structure to see how she synthesized her subject matter because she had two separate block periods with these 6th graders.

There were two instances here that tie to these 10 precepts:

On September 11, she had a “Do Now” that drew on the student’s prior knowledge. She clearly was trying to plug cultural relevancy to the calendar, despite none of the students being old enough to experience 9/11. Some shared “My parents said this” or “My relatives were in New York” or “I know someone who knew someone on the plane.” My mentor teacher replied “Great answer ___” to all the white children sharing. And then the Muslim student raised his hand.

“My family has experienced discrimination since 9/11. People blame my culture for what happened even though I’m Muslim. Bush sent troops to Iraq and people died. But what about those innocent lives in Iraq?”

6th grader, 2016

The teacher said “Okay, great everyone thank you for sharing” And the history lesson moved back to Mesopotamians or something.

Another instance was when students discussed police brutality from the 2016 presidential debates. A student brought up stop-and-frisk discourse and said, “it’s about the ‘pat and frisk’ thing. Because cops are pulling blacks and latinos over because of their color”

And the teacher replied, ” It’s not that simple, we don’t want to overgeneralize”

Mentor Teacher ,2016

The other instance was around the time San Francisco began shifting from Christopher Columbus day to Indigenous People’s Day. Again, I think my mentor was trying to draw on prior knowledge from the students. A “Do Now” asking students to share what they know about Christopher Columbus and why we would dedicate a day to him. Many students talked about Thanksgiving. Or how he ‘discovered’ America. And then the young black scholar spoke out and shared, “But didn’t Christopher Columbus bring disease and kill all the Native Americans?”

The teacher corrected him and said, “Not Native Americans, Indians.”

The student brings up “didn’t he kill and make slaves of them?”

The teacher ends the discussion with “There’s a lot of controversy around it”

What I originally intended to do with this post back in Janaury 2020 was to break down each of these precepts and make some connections with the stories I would’ve told:

#1 Fully responsive/unpacking what students say or share

- In both instances, this teacher did not fully respond or unpack what these students shared. Their experience or responses were rich with knowledge/truth but she denied them that opportunity to teach what they know.

- When I teach now, I try to provide more space for students to interpret, share, and analyze together.

#2 Connect their classroom and academics to their lives outside of school

- This is deeply embedded in the topics I choose to teach. Though it was passed on from my master teacher, I firmly believe that topics like systemic oppression, immigration, or even literary theory are relevant. These topics allow students to begin “learning about the world around you, learning about your place in it, learning about the lives of other people…so that you can better contextualize your life in community” —John Green

#3 Culturally Responsive Pedagogy/sensitivity to students’ identities

- With the 9/11 anecdote, the student was being vulnerable about racial discrimination and islamophobia, but the teacher dismissed the learning opportunity from his story.

#4 Brave Space

- When I was in college, “safe space” became more of a buzzword than it did the space itself. The same could apply to “brave space” today. But at the time, I wanted to create a space where students felt brave enough to speak out and share their knowledge. The space itself should be safe enough for them to be brave.

#5 Reflect

- Reflection has been a huge proponent in my growth as a student and teacher today. I believe it’s important for students to look back and have introspection. Guiding them through reflection eventually leads to growth and self-determination of themselves.

#6 Gradual Release of Responsibility, #7 Accessibility/multiple ways of participating in the lesson, #8 Challenging students to exceed their capabilities

- This may have changed over the past few years, but the goal here was to transfer the theory to practice that it became less guided practice and eventually more independent student action. This is now evident through the self-pacing model I use now. The model itself has various entry points and combines all lessons/activities I use. But I’ll save that for another post.

- I chose these three precepts because [#6] I was taught that the best teaching practices follow this guideline. Eventually transferring the knowledge by modeling and then somehow classroom managing 35 kids to do the same in less than half an hour.

- [#7] Again, from training or grad classes, I learned that learning needs to be accessible from Sped to EL, hard copy to digital. There need to be various ways for students to learn because of the endless ways people learn.

- [#8] And I know that myself as a student was challenged enough. But I know with the right guidance and rapport with a teacher, I could have done better. That was evident in my college experience.

#9

- This also ties to the model I previously mentioned. It focuses on a mastery-based grading strategy that allows students to try again.

- I initially chose this as a precept because I learned best from the many mistakes I made. Mistakes are the first step to learning. And I want students to know that before they’re marked as a failure or not given another chance.

#10 Your voice always matters

- This is definitely something I took from my time with PEP (Pin@y Educational Partnerships) that eventually became embedded in my curriculum. Many of the stories I teach include the power/agency in our voice.

- I never thought my voice mattered until someone showed me how it could, even in the eyes of history. And I felt empowered to show my students the same.

Epilogue:

I’m pretty sure I could go on about these ten precepts. If not expand, change, or even add more. But as I close out revisiting an old piece. I think these precepts should remain as a reflection. And anything new could have its own space. Maybe I will make a new ten precepts for my teaching now. Consisting of things I learned. It’s important to look back on where I started. And attest to the foundation in my teaching pedagogy. It’s been a fast six years since I wrote these precepts. I almost forgot that there was a time when I didn’t think critically of the world. Of education. Or any systematic issues before I found teaching.

This is a testament to where I started and how I carry those things with me now.